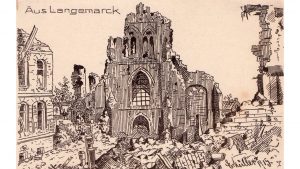

Sure, anything in the “strip of murdered nature” that was the battlefields of the Western Front was going to end up as rubble. But there are RGA War Diaries that record their target as “Langemarck Church” not a strong point in the church, or the village but the church itself. It was repeatedly targeted along with targets such as “trenches u.16.d.76.23- u 16 d.54.14 and “wire u 16 a.52,05 – u16 a.15.16” So why was the church such a popular target?

A week or so ago I was carrying out some research for a guided family history tour to the battlefields of where their relative Bombardier Griffiths had served in 324 Heavy battery RGA. The battery’s war diaries were available, but the diary for March 1918, the month he died, was missing. Furthermore, there was evidence that suggested that Bombardier Griffiths did not join 324 battery until January 1918.

However, the diaries were very legible and full, recording the details of each shoot, including rounds fired and the target.

324 Heavy Battery was formed from 1916 conscripts and deployed to France in May 1917 equipped with four 6″ 26 cwt Howitzers. After a few weeks on the quiet sector of Bois Grenier the battery moved to Woesten, north of Ieper on 14th July 1917. From there it took part in the preliminary bombardment for the 31 St July , then stepping forwards to Elverdinge. The first day of 3rd Ypres 31st July, was successful on Pilckem Ridge, with the British line moving forward roughly along the Steenbeek south west of Langemarck.

A first world war artillery piece aimed at a target some 6km away was probably going to miss with its first round, even if the target had been plotted on a surveyed trench map. The position of the guns and the direction in which they are recorded as pointing may not be particularly accurate. Changes in the wind speed and direction will change the trajectory. An observer with communications to the guns could adjust the fire of the guns until the rounds form the guns are landing in the target area. Of course, by this the enemy will have worked out what was going to happen next and take cover.

A further problem is that the guns in a battery would not all have the same characteristics. Guns may be manufactured to different standards and might have different wear in the barrel. The WD entry for 5th August records that between 2pm and 2.30 pm 324 battery fired 30 rounds unobserved at Langemarck Church as ordered in Operation Order No 23. After this, someone,at Periscope House, probably Major William Orpen Sikottowe Sanders, the battery commander decided to calibrate the guns using the church. Firing ten rounds and watching one hit the church with others plus and minus, the unit could apply a correction for each gun. (Though ten rounds might be few to base a statistically reliable.

A further problem is that the guns in a battery would not all have the same characteristics. Guns may be manufactured to different standards and might have different wear in the barrel. The WD entry for 5th August records that between 2pm and 2.30 pm 324 battery fired 30 rounds unobserved at Langemarck Church as ordered in Operation Order No 23. After this, someone,at Periscope House, probably Major William Orpen Sikottowe Sanders, the battery commander decided to calibrate the guns using the church. Firing ten rounds and watching one hit the church with others plus and minus, the unit could apply a correction for each gun. (Though ten rounds might be few to base a statistically reliable.

It wasn’t always possible to see targets clearly. Pilckem ridge isn’t much higher than the surrounding ground and it would have been quite difficult to pick out specific targets from the ground. Furthermore, the landscape was devastated, with buildings and trees leveled and landmarks obliterated.

One technique which could help is to use a “Witness Point” This was a point some distance from a target, but accurately located in relation to it, which could be ranged without losing surprise against the target and the correction applied to data for the target. If the correction to hit the church was “left a bit and add a bit”, the same correction could ensure that targets in the same area picked off a map could be hit first time.

The entry for 7th August shows that between 3.30 and 6.30pm 324 battery fired a total of 24rounds at Langemarck Church as a Witness Point. Their next shoot 7.30pm to 8.30 an unobserved concentration on trenches straddling the Langemarck-Poelcapelle road was unobserved, but could be expected to be reasonably accurate, as might the shoot at 9pm. a response to a call for the SOS.

The targets on the 8th August were east and west of the German positions which ran through the north end of the German Cemetery at Langemarck, as evidenced by the three bunkers.

The search for the part an individual soldier played turns up some surprising detail about how the battle was fought and the reason why Langemarck Church was shelled. It also explain the rationale that supports the old military axiom to never deploy at an obvious terrain feature. Landmarks are shelled because they are landmarks .